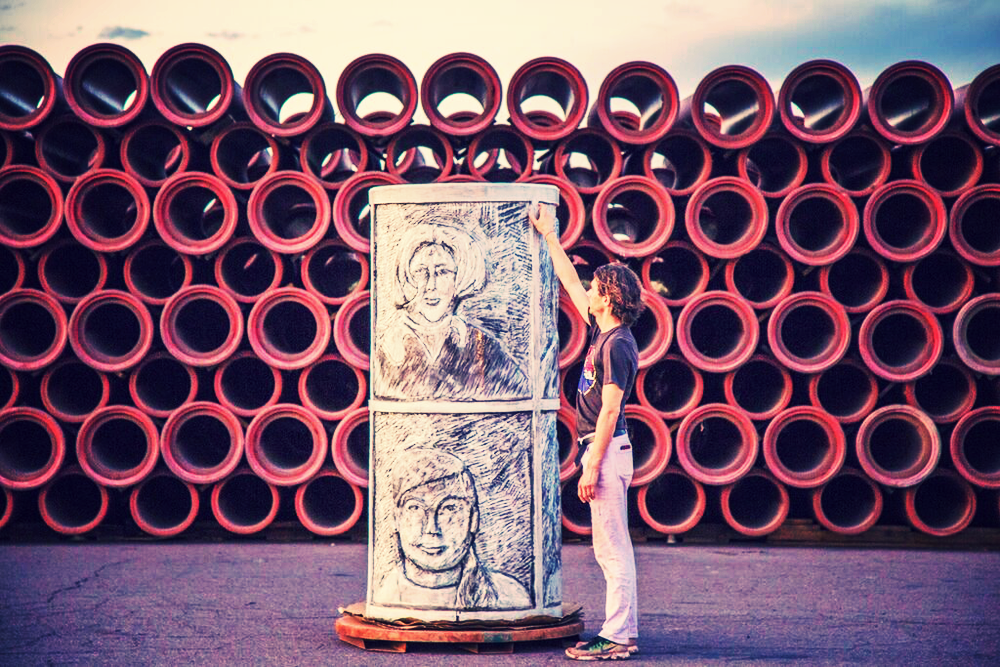

Writer Profile: Yelena Moskovich

Imaginative, beguiling, perplexing, daring—writer Yelena Moskovich made a distinct splash into the literary world with her debut novel The Natashas (Serpent's Tail UK, 2016). With an atmosphere evocative of David Lynch, Murakami and Angela Carter, The Natashas is a surreal exploration of identity and sexuality that pull three seemingly disparate worlds together like dissonant strings. Béatrice is a jazz singer struggling for autonomy over her body that bares nicknames such as “Miss Monroe.” César is a Mexican actor grappling with his sexuality and profession. But the boundaries between realities blur as Béatrice begins a love affair with Polina whose existence is elusive, and César disappears into a violent acting role. Surrounding these narratives is a windowless room inhabited by a chorus of sex-trafficked women all named Natasha. The tension between selves; internal and external, self-perpetuated and inherited, is explored with stunning and original prose. Cigarette smoke “crashes like watercolors” against a wall, César pulls traits for his characters from his own depths, “like a white hair from a bowl of milk.” A feminist novel that rebels against type and structure, Yelena Moskovich has established herself as an intriguing and atypical new voice in fiction.

Yelena Moskovich was born into a Jewish family living in the Ukraine under the Soviet Union. When its fall became imminent, her family seized the opportunity to escape the anti-Semitism and corruption that had pervaded their lives for the sake of Yelena and her brother; both children at the time. A journey that directed the family towards Israel at first; a last minute change of plans sent them to the United States—to Wisconsin, of all places. Then Moskovich continued on her own, to Boston, then to Paris; the city she now calls home. As Moskovich is an explorer of internal worlds, and her personal voyage follows suit.

The Natashas was listed on The Guardian’s Best Books of 2016, The Telegraph’s Best Debuts of 2016 and The Irish Times 'Our Favorite Books of 2016'. To celebrate the U.S. publication of The Natashas (Dzanc Book), Rogue sits down with Yelena Moskovich to discuss the book and her own incredible journey.

ROGUE: The Natashas blurs the line between dreams and waking life in such a multi-dimensional way. The Natashas are a chorus of trafficked women existing around the two main characters; César and Béatrice. How do these realities intertwine in the book?

Moskovich: The book happens on three planes. There’s “reality” or whatever we know, the things that we can touch and locate somewhere in the world. Then there’s a kind of surreal dreamlike space that I call the psycho-fantasmatique world, and I like that word because it’s a space that exists in both dreams and in reality. It’s not that it turns off when you wake up—it’s still there— our psyche is still present but in different ways. Either subconsciously or with a different coding. And the third plane is a philosophical bubble that I call—espace de ridicule. Because for me, a philosophical space is where you can ridicule something in a real way, this happens a lot in the room of the Natashas. They’re either a clown show or Greek chorus. It’s the room where philosophy can happen because our pain and desires can be ridiculous and we can turn ourselves inside out like a sock.

What is it about the ridiculous or humor that allows philosophical conversations to have more poignancy?

I remember when we’d go deep into French philosophy like Derrida in school, for example the between différance and différence. We’d get so in there like "it’s the e…and what happens when you take it out?" Philosophy is such a clown show. It’s the same way that Monique Wittig, the feminist philosopher, writes je (“I” in French) in her novel The Lesbian Body. She puts a slash between the J and E which makes "j/e." It’s about the refusal of the "I" that I have to inherit so I cut the "I" and make a different "I." There are whole essays and studies about her use of "j/e." And the translators go crazy—"like how do we translate that? When we have only 'I,’ it’s only one letter!" (laughs) So there was all this debate. And I loved that—you have to do that to go into a topic but the more serious you get, the more ridiculous it becomes because you’re focusing on the pinhead of a pinhead of a pinhead. That’s why in The Natashas—I love those moments when they’re going to really focus on what a papaya is, something that you think is a throwaway thing, like the photos of Marilyn Monroe. They’re not difficult concepts but it becomes as complex as Derrida’s différance.

The Natashas are trafficked women. How much research did you do on sex trafficking to create this bubble?

I was writing these scenes about a group of women living in a windowless room. Then all of a sudden I realized they all had the same name. I don’t where I got the name Natasha but I knew they should all be Natasha. Then I stumbled on Victor Malareck’s The Natashas: Inside the New Global Sex Trade. There was tons of stuff I ended up reading like Anna’s Land which is a collection of essays from the point of view of trafficked women. I didn’t want to make it about sex trafficking but at the same time, I fell into a huge world—especially on the internet. In the book I mention that there is a highway between Dresden and Prague where you can get the cheapest prostitutes of Europe. I found that out on this online forum like "rate your favorite prostitute off the European highway" type of site. And people were really open, saying "this is where you need to go for her." "If she charges you this she’s a bitch," "she gave it to me for 25…" but then the thing that was really intense…they communicated with each other. "If you see that girl, slap her" because one of the recurring complaints from these men was over whether she does it like she means it or likes it. And they refuse to understand…that they don’t. They had no clue. And the anger that came out…this one guy got so angry about this girl refusing to kiss him. But as you know I was working for a historical NGO in Paris at the time that did research on genocide and mass crimes, so I had to limit myself as to how much heavy subject matter I was willing to let in.

What did you take away from your research that you included in the book?

First of all, those little details. Like how they got here. How they were rolled up in a carpet and put in a truck. But also, I found that it helped me be like a wet towel and throw myself in the blood, tears and misery—it’s really heavy shit. And it helped me find a lot of the comedy and clownesque stuff in the process of ringing it out. You can’t just flop it back at the reader, I mean you can, but I’m not throwing Schindler's List like— "back at ya!" You know? (laughs) My goal reminds me of this line from Russian poet Anna Akhtamova: "from what muck poetry grows…" And I always keep that in mind especially when I’m working with heavy subjects. The muck, the shit, the hard, shocking, "she was raped with a knife!" that type of stuff—what is a reader going to do with that? Other than be shocked? And maybe that’s what I learned from reading mass crime scenes —at a certain point it’s like "what I do with this?" How does this grow in the garden? How does this become poetry or useful for someone else? That process of ringing it out, finding the comedy, is a catharsis.

The body is a central theme in the book—what is that tension between being attached to and detached from the body? Are the Natashas women who are not present in their bodies? There but not there?

The main line that I really used to pull the whole thing together is when Polina says: "there are people who leave their bodies and their bodies go on living without them. These people are called Natasha." There are definite concrete people who are deprived of agency over their body in a very direct way and there are many levels of that. They still feel pain but their body and soul is blurry and out of focus.

In my second book I go into this theme a lot more. People who are the throwaways. These types of people, the only way they can be integrated into society is to disrupt language as a whole. These are the transgressive, rebellious, they are going to clash in how they express themselves through their body and words. In creating these spaces, there is something about welcoming or stimulating that sort of encounter, without it necessarily having to be violent.

What about your second novel...how’s that going?

It's tricky because this book has such a winding and twisting structure and mixes together some political history. It's called Virtuoso (Serpent's Tail, 2019) and it takes place in post-communist Prague. Two throwaways, unwanted girls, Jana and Zorka, struggle against their society through a mutual disobedience. Years later, Jana is a Czech interpreter in Paris. Working at a medical trade show she catches the eyes of Aimée, the daughter of a prominent prosthetics specialist. It's about first loves, lost loves, a clan of homesick children who invade the body through the anus, a keychain of histories, and the newest hospital mattress designed to sustain critical patients between life and death, named Virtuoso.

Are there recurring running themes running through both The Natashas and Virtuoso?

They both cover intimacy and the intensity of your feelings not fitting into the society that you’re in. In The Natashas, you’re looking outside of it. Virtuoso is not as voyeuristic. The reader is more inside of it, up close.

How did you get here? You currently live in Paris, were born in the Ukraine and grew up in Wisconsin in the United States.

I was born Kharkiv, on northeast border between Ukraine and Russia, when it was still all the Soviet Union, at the cusp of the Gorbachev era. Censorship in the Soviet Union was beginning to crack; books were being able to be published, there was more communication overall and then it fell in 1991. I was seven. My parents took me out of school at six but we ended up waiting a year, thinking we’re going to leave at any moment. I don’t even know what I did that year. As Jews, the easiest place to get entry was Israel, so we had shipped part of our stuff to Israel, then we ended up coming to the States. My grandfather didn’t want to ruin our chances of getting into the US by applying with us, because he was a teacher, and as a teacher, he was obligated to be part of the Communist Party (protocole more than dogma) and as you know America wasn’t so keen on communists...I remember my grandfather telling me that all teachers had a quota of how many times per class they had to give credit to Stalin. Even if you were teaching things like literature or science or molecules, you’d have say, "that is why our great father Stalin helped manifest electricity…" you had to link him to every lesson. (laughs) And there were people that would check up on you, ask the students—"did the teacher mention Stalin?"

Speaking of the space of ridiculousness…

(laughs) Yeah.

How does that absurdism relate to Eastern European and Russian literature?

The thing about absurdism and that moment that became so big in Europe mainly after WWII, this disillusionment, the clash between us, understanding that life has no specific meaning or purpose but as a human being we cannot live life without meaning and purpose—that paradox. It’s not that life is logically impossible, but humanly impossible. That sort of tension is replicated in a lot of microcosms with heavy censorship.

How did you get to the United States?

My dad had an uncle in America who helped us get our papers. Of course no one asked me if I wanted to go or not, I was just a kid. But I remember overhearing that American had dolls that could move their elbows. And I was like "shut your face...it cannot be!" And they were like "oh and you know what else? Some of the dolls can close their eyes." And I was like—"THAT! That is NOT TRUE! Too much!" (laughs) I feel like we entered the industrial revolution when we landed in Chicago. Not only was I little, but in the Soviet Union, they never really showed you that a whole world outside of the USSR existed. I mean I had no idea. We didn’t know what it looked like, what it sounded like. I didn’t know that there were people with different colored skin, that spoke different languages. I kinda assumed everyone spoke Russian. Our map of the world was RUSSIA in the center with these little spots of color like over there. I remember when I landed…I felt like I stepped off the edge of the world.

Around that period of time, do you know how many immigrated to the US?

I don’t know—I think the biggest number are Jews. The first wave was around the Bolshevik Revolution and then the fall of the Soviet Union.

Have you gotten any impression that people in the United States have any kind of knowledge about what happened?

To be honest, I’m not going to belittle Americans on this point as kind of an American myself. Even with my encounters with Russians in Paris, when I would mention a little something about Russia being anti-Semitic…was anti-Semitic…maybe is…ok I’m not going to argue (laughs) but it was. It was. On my passport, my nationality was marked Jewish, not Russian. We were considered foreigners, that’s a fact not just a feeling. But there are Russians I’ll meet today who will say, "don’t be so sensitive…" It’s my perspective. People have different realities, not just Americans.

Who sponsored your family?

It’s a tricky subject. I don’t know how all Jewish refugees got in but a lot of them were eventually linked into a Lubavitch community. Some people dispute they’re cultish and weird, but they do a lot of good things and helped a lot of immigrants like us. So my uncle put in a little money, but most of the money they put in which we had to pay back. Nothing was free nor given; we were indebted for years. And part of the deal was that they taught us about Judaism since you know, that was our main deprivation. (laughs) And we were atheist; we just wanted to live in a free country. So I was put in an orthodox school, my dad and brother had to get circumcised. Plop! "You’re Jewish." And they build their community like that; a lot of these people stayed in the system, but we left.

What was it like going from an orthodox to a public school…?

Yeah the Midwest. The orthodox school was all white Jews...really organized, girls and boys separated. And then I go to this public school and there were Hispanic and black people…and you have to know where and how you fit in...how do you dress, how are you going to talk, who do you hang with, how are you going to present yourself? Russian immigrants sort of went with other Russians, but I really never associated with that click. I still had my ascent so I took on the Hispanic accent at one point (laughs) because it wasn’t that big of a stretch to change accents. I understood accents.

The idea of presenting yourself...would you say its a cultural attribute of the United States that isn’t present in Russian culture?

I don’t want to sound like a Marxist…

Haha.

...I think it's a symptom of the capitalist euphoria which is funny, about my mom, maybe you shouldn't print this because my mom will deny it happened but—it DID. (laughs) When I came out to my mom that I was a lesbian, she basically implied that it was capitalism that made me gay. "Too many choices," she said. (laughs) "In Russia, we have no choice, you just know. You give someone too many choice, it is confusing…"

To piggyback off that, how is sexuality explored in the novel? César is gay but that expression is inhibited, partially due to the cultural stigma attached, and Béatrice has relationships with men but feels detached then begins an affair with a woman. Did you draw from your own experiences?

Beatrice’s sexuality is the most elusive. We don’t even know how real she is to herself. It wasn’t a conscious choice that I made...but when I think about intimacy, I can’t help but write about what it means to desire in between the lines because that’s how I grew up. I don’t know, it stays in your body. The restrictions...how you first learn how to touch, to go for what you want. Now in Paris, I can be publicly affectionate almost anywhere but I’m still aware that I’m being looked at. There’s a film of outrage that sometimes escapes my gentle intimate touches because when I touch someone, it can’t be just between us—someone is always looking. It does fill me with outrage and anger. And that kind of frustration becomes internalized.

Both César and Béatrice have very real romantic relationships with two characters that are “invented.” Are they reflections of themselves?

I was trying to be as careful as I could. I didn’t want them to be purely symbolic because so often homosexuality in books, especially between women, becomes "oh they just wanna be each other." But naturally between us all, we’re going to project and see ourselves in the other. The elusiveness of both their relationships, however, is in its "fictionalness"…whether a person is real or not. Manny is definitely fiction and Polina maybe. It’s more about the fictionality of intimacy. Also, it goes back to the standard. As soon as you have a minority or gay character, then that means they are going to confront their “gayness” or “blackness…” etc. Yes the book talks about sexuality but they’re grappling with other things…the fragmentation that happens from traumatic instances.

Why do you think you’ve been compared to Murakami and Lynch?

It goes back to the psycho-fantasmatique place. And jouissance (a sublime pleasure or orgasm)—that almost orgasmic feeling when something can be broken apart and no longer obligated to fit into conventional meaning. There’s something very playful about that. There are two camps of Lynch: "one, that’s a crazy movie!" And then, the other, people who use it like a playground. Same with Murakami…gleefulness, jouissance—it’s a relief from the impossibility of life. Maybe life doesn’t have a set meaning and it doesn’t have to. Both of those artists give space for this and I hope I do as well.

Have you heard responses to your novel from a feminist slant?

I think a lot of the critics that wrote about it have been either women or men with that perspective already. One woman asked me if I would consider this as a political book…I think all books are political, but some books don’t know that they are. Lauren Elkin from The Financial Times said that in the book I find the perfect balance between aesthetics and outrage—that hits it on the nail.

Where was the outrage directed?

My intentional outrage was more expressed structurally. Hélène Cixous—the French feminist—has a line that I keep close to me when I write. "Women must write as if there is no one to correct them." Something like that. That is inherently feminist. There is the concept and content but also the format and structure. For me, it was about being able to find it for myself—rather than just inheriting the given plot structure. Part of the outrage is expressed in the information that is withheld and the scenes that clash—pulling things in directions that you aren’t expecting.

In your writing, you go into places in the psyche that we don’t normally go to or not openly anyway. How did you treat those charged and triggering psychological spaces?

When I was writing it, I wanted to be really careful. I didn’t want to just shock people… I think the true freedom of speech and transgression of censorship is when you can go into the subtlety and complexity of something rather than boldly say the contrary. Like, "oh you can’t say Penis?? Well—PENIS!!" How do you start to unravel something delicately, so you don't get an answer at the end, but rather continue asking the question more and more for yourself. Not to get too cliché.

As Moskovich began her career as a playwright and physical theatre performer, a theatricality turns the three planes of The Natashas into stages where trauma and tragedy play out their dark comedy and catharsis. The book has stirred the fascination of many critics and audiences in both English and French (Editions Viviane Hamy, 2017) and Moskovich has recently completed her first U.S. book tour. The Natashas is a playground for the psyche to explore itself; haunting and comedic in its innocence and imagination. Multiple languages, cultural influences and current themes such as sex-trafficking create a startling portrait of our modern era.

Written by Maria Mocerino

Photography by Ida Skovmand, Marianne Katser

and Inès Manai