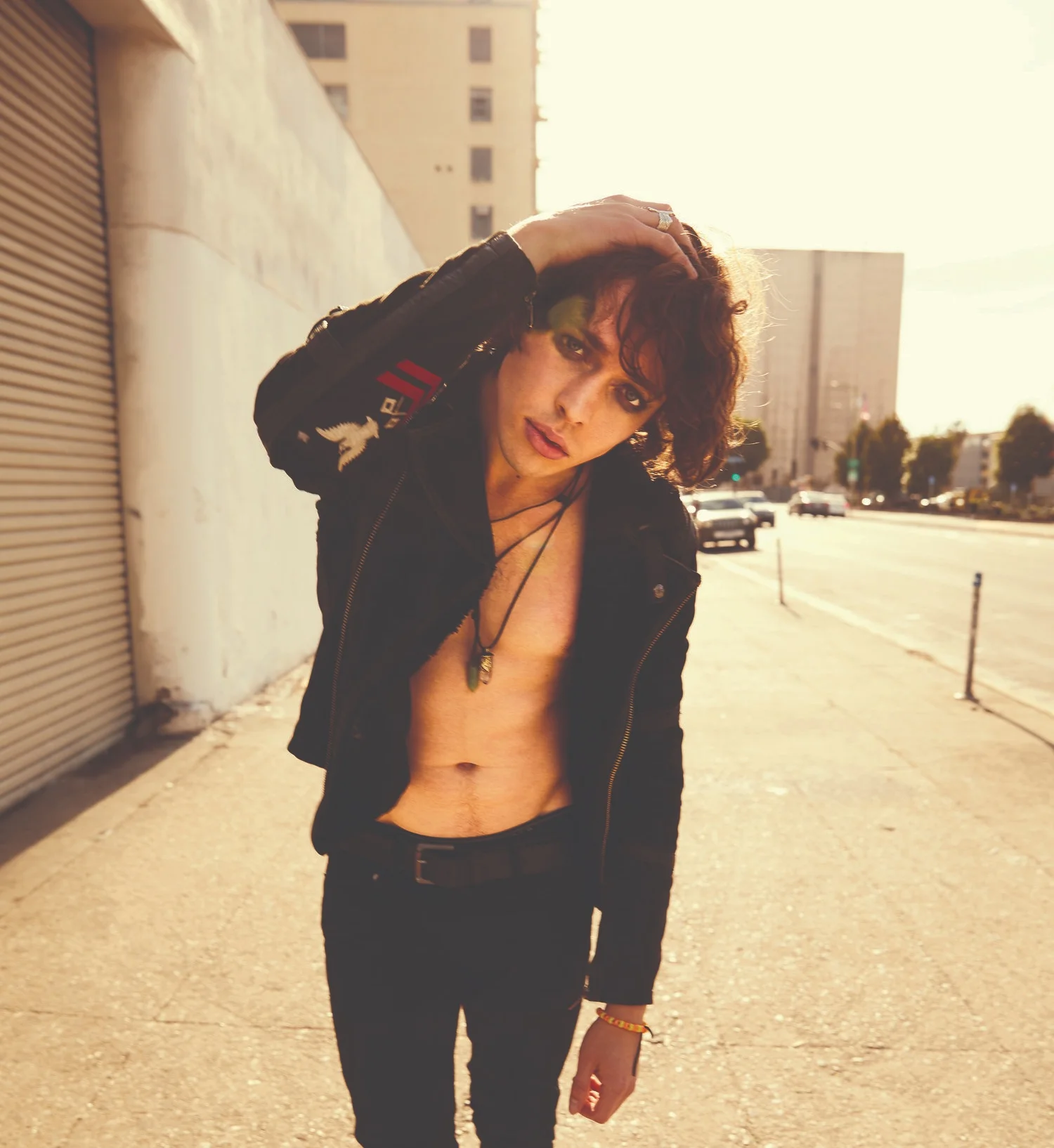

Doe Paoro

Doe Paoro is a force to be reckoned with. With a deeply complex musicianship, she takes listeners on a journey only she knows the pathways through. By imbuing sounds and techniques outside of the realm of normalcy, she crafts a sound that is uniquely her own. Paoro is fresh off the release of her sophomore album, After, which we are happy to admit did not fall victim to the ever-famous sophomore slump. Rogue chats with the musician about her training in Tibetan folk opera, writing from a place of fulfillment, and why Minneapolis has been turning into an unlikely musician's paradise.

There's a lot of different sounds and influences on the album. What are some new things you experimented with bringing to the table for this one?

Patience. After took three years to make whereas my first record, Slow to Love, took only six months. A lot can happen in three years, and I think the variety of influences reflects the seasons, experiences, landscapes, music, and art that I was exposed to in that period. You can hear the passage of time and turning of the seasons in the record, if you listen for it.

“Walking Backward," “Untethered," and "Nobody" all have their own distinct sounds yet still work cohesively. How was the process in crafting these different sonic experiences? Were they recorded similar in time to each other or were they written during different periods?

They were all recorded in the same period of time, but written during various times over the three years. The challenge in this record, from a production standpoint, was finding the common thread in all the songs since they span a wide range in mood and genre. It helped that both of the producers and many of the musicians on the record had worked together previously, so they already had a cohesive collective aesthetic and flow of ideas.

You've studied Tibetan folk opera. Can you talk a bit about that process and how subsequent trips continued to expand your range of musicality?

I’ve been to India three times in the past four years to study Tibetan opera, or lhamo, with a teacher in the village of McLeod Ganj, where many Tibetans live in exile. The first time I heard Tibetan opera, I was stunned—I didn’t realize it was possible for the human voice to make such sounds. I learned how to control my breath in certain ways and that new awareness connected me to the meditative aspects of singing. Mostly, I think it’s affected my willingness to experiment with form in a song structure. A mantra is a song. So is a piece with two unique verses and a bridge. It can be anything.

You've mentioned wanting to write from a place of fulfillment for After. How does that differ from where you used to write?

In the past, I’ve turned to writing music in moments of perceived personal loss as a path to healing. I want to find other gateways to inspiration; I don’t want to depend on sadness to write. It’s not a narrative I’m comfortable identifying with.

Different seasons are reflected in the songs. Did you know what season each would cover when writing or was that something that came organically as you were recording?

I don’t plan out my songs that deliberately; I sort of just absorb and then produce, and what comes out comes out. Usually it reflects whatever climate I’m in.

What was the criteria for a song making it onto the album? How did you narrow it down from 40 to 10? Were there former versions of After or is the one releasing now the first time it felt truly complete?

The producers listened through all 40 demos and helped me pick. We narrowed it down and produced 14, and then decided on the 10 strongest ones. I may release some of the other songs down the line.

If you were to paint a picture to illustrate the album, what would it be of and what would the style be?

Like a Klimt.

The album was largely recorded in Minneapolis & Wisconsin. What kind of effect did this have on getting into the creative headspace, if it did at all?

There is a really interesting thing happening in Minneapolis with music. The cost of living is low, so people don’t have to run themselves out to make rent and they can devote more time and energy to their artistic and creative pursuits. There is less pressure to make something that’s commercially viable, which means there is more room for experimentation. It’s also missing a lot of the vanity that characterizes cities like New York or Los Angeles.

I really appreciated this in the recording process—it was very easy to be in touch with my music and the process, and shut down outside distractions.

What was the vibe like in the studio? Fifteen other artists are credited on the album, including your upcoming tourmates. Were they involved in the songwriting process or did you involve them only after the production process was complete?

The vibe was very relaxed. There were musicians passing through all the time, working on their own records, and a lot of them ended up cameoing on mine. Josh LeBlanc from the Givers—with whom I’ll be touring in November—plays trumpet on a few tracks. Nick and Amelia from Sylvan Esso added bass and vocals, and of course all the guys from Bon Iver were working on the record. With the exception of Adam Rhodes, my bandmate, most of the musicians who were involved in the recording were not involved in the songwriting.

What are three things necessary for your happiness?

Love. Possibility. Sleep.

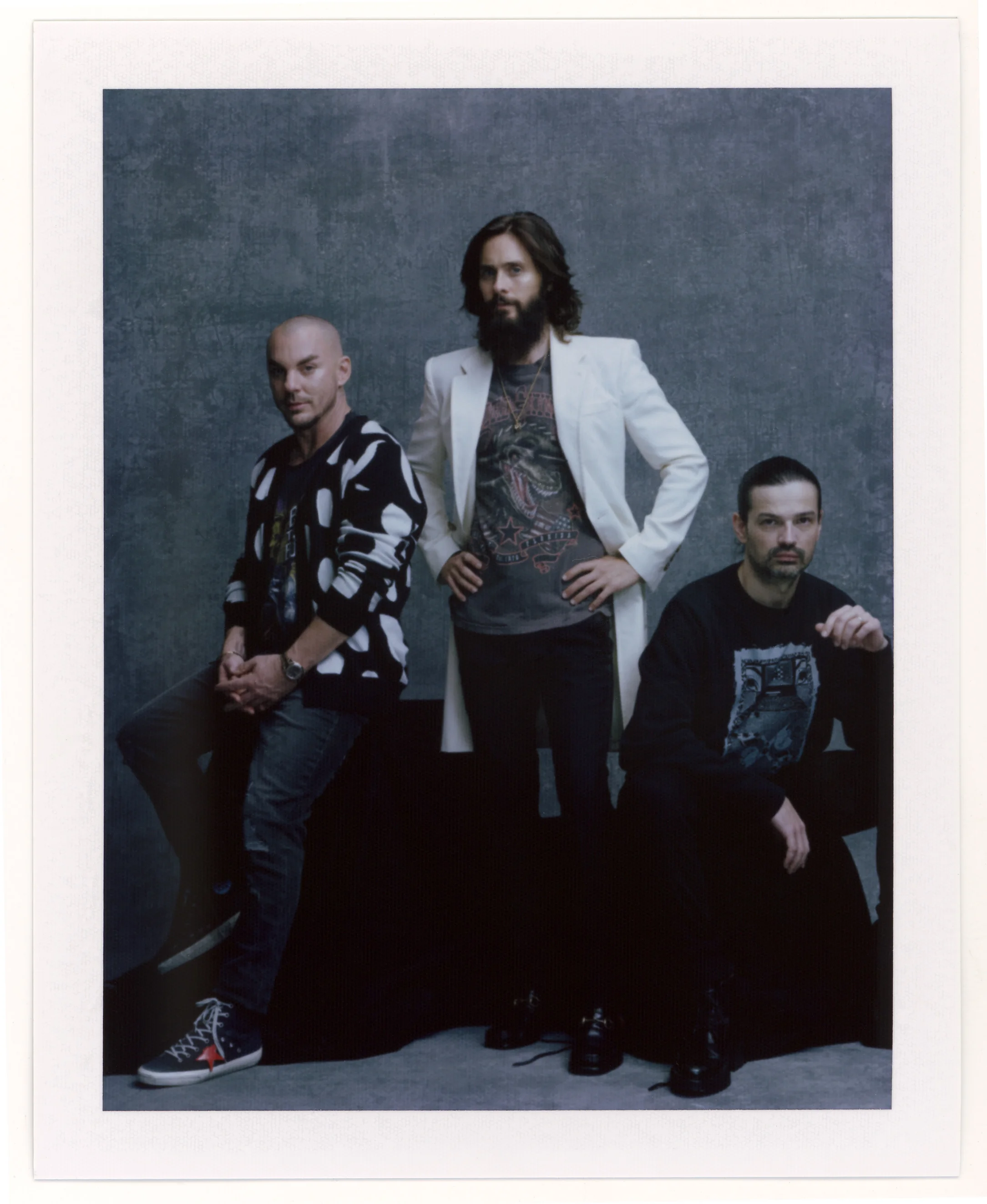

Photography by David Lekach

Interview by Jordan Blakeman